The three centuries following Ferdinand Magellan’s inaugural circumnavigatory voyage in the early 1500s saw most seafaring European countries attempting ambitious expeditions of their own. However, it was often sailors’ aquatic search for land that reaffirmed what historian Joyce Chaplin has called their “terrestriality”: many voyages during this period were years-long, arduous trips that tallied hundreds of deaths among crew due to ever-threatening illnesses like scurvy. Enter “portable soup”—a thin, dehydrated tablet often made from the boiled meat and bones of cattle. A seemingly unformidable challenger to the beast of mortality, portable soup became an esculent savior that preserved, and therefore transformed, sailors’ lives.

The three centuries following Ferdinand Magellan’s inaugural circumnavigatory voyage in the early 1500s saw most seafaring European countries attempting ambitious expeditions of their own. However, it was often sailors’ aquatic search for land that reaffirmed what historian Joyce Chaplin has called their “terrestriality”: many voyages during this period were years-long, arduous trips that tallied hundreds of deaths among crew due to ever-threatening illnesses like scurvy. Enter “portable soup”—a thin, dehydrated tablet often made from the boiled meat and bones of cattle. A seemingly unformidable challenger to the beast of mortality, portable soup became an esculent savior that preserved, and therefore transformed, sailors’ lives.

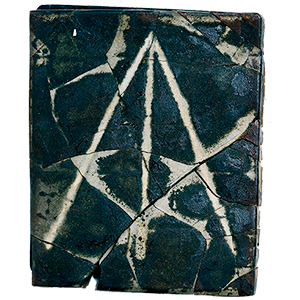

An antecedent of bouillon cubes, a block of portable soup—like the one pictured here, held by Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum—is a portion of cattle beef boiled to a dehydrated, glue-like consistency which typically also contained or was served with vegetables, thought essential to scurvy prevention. Portable soup’s conception played a mysterious yet much-touted role in the success of John Byron’s record-setting circumnavigation as captain of the HMS Dolphin: his journey, beginning in 1764, took only 22 months and cost relatively few lives among the 153 sailors on board.

The portable soup, sometimes called pocket soup, was used as a weapon against scurvy—and popularized as such by navigators like James Cook and William Bligh. In fact, in 1754, Dr. James Lind suggested the “antiscorbutic” soup be manufactured for the Royal Navy. But among sailors and scientists, doubt prevailed about whether the soup itself provided health benefits or simply made the foods it accompanied, like green vegetables, flavorful and bearable to eat for men with scurvy-sore gums.

Seemingly humble and quaint, portable soup was a tool of empire. Invented to survive long, dangerous journeys, the extant specimen of soup largely owes its centuries-long existence to its inherent portability, along with other shelf-stable voyage foods like ship’s biscuit. The item is dehydrated, which forestalls its decay. In fact, it has deteriorated so minimally that when Sir Jack Drummond, a consultant for the British Food Ministry, cut and sampled a corner of the soup in the 1930s, he reported that it was still edible. Voyages like Captain Cook’s became historically regarded as “floating laboratories for the testing of various [antiscorbutic] foods,” in the words of Janet Clarkson. The notion of a ship as a laboratory—an incubator for scientific experimentation—suggests a lavish, multilayered vision for Cook’s voyage: a vessel endowed with both geographic and scientific purposes for national advancement. In its time, the soup was engineered by a powerful empire with the means to manufacture an item in bulk that successfully defies the perishable nature of food; now, it continues to persist in a royal institution that is itself a custodian of imperial history and objects. Perhaps this soup’s survival is proof that it is frequently non-imperial foods that are lost to ephemerality, and the edibles of empire that remain.

As if the product itself was not meant to fuel the thefts of the men who ate it, the block of soup is marked with a hand-drawn arrow to indicate its officiality as government property, likely to discourage sailors, ever hungry, from stealing more than their ration. Indeed, rations were generous; for distributing the portable soup in seemingly infinite supply to his crew, Byron was revered. To his shipmates, this was a display of “great humanity,” representative of the “honour of that humane Commander [under whom] the Dolphin… encompassed the earth.”

Image: Portable Soup, mid to late 18th century, © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (Object AAB0012).

This article was written by C.C. Lucas. For more information about her work and her other contributions to The Kitchen in the Cabinet click here.

This article was written by C.C. Lucas. For more information about her work and her other contributions to The Kitchen in the Cabinet click here.

References

A Voyage Round the World, In His Majesty’s Ship The Dolphin, Commanded by the Honourable Commodore Byron. London, 1767.

Baron, Jeremy Hugh. “Sailors’ Scurvy Before and After James Lind—A Reassessment.” Nutrition Reviews 67, no. 6 (June 2009): 315–32.

Bartholemew, Michael. “James Lind’s Treatise on the Scurvy (1753).” Postgraduate Medical Journal 78 (2002): 695–696.

Carpenter, Kenneth J. The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. 66.

Circumnavigation of the Globe and Progress of Maritime Discovery from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. London, 1859.

Clarkson, Janet. Soup: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books, 2010.

Chaplin, Joyce E. Round about the Earth: Circumnavigation from Magellan to Orbit. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012. 120–124.

Chaplin, Joyce E. “Terrestriality.” The Appendix. April 10, 2014. http://theappendix.net/issues/2014/4/terrestriality.

Cook, James. “The Method Taken for Preserving the Health of the Crew of His Majesty’s Ship the Resolution during Her Late Voyage Round the World.” Philosophical Transactions 66 (1776): 402–406.

Fictum, David. “Salt, Pork, Ship’s Biscuit, and Burgoo: Sea Provisions for Common Sailors and Pirates.” January 2016. https://csphistorical.com/2016/01/24/salt-pork-ships-biscuit-and-burgoo-sea-provisions-for-common-sailors-and-pirates-part-1/.

Gallagher, Robert E. Byron’s Journal of His Circumnavigation, 1764–1766. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964.

McLeod, A.B. British Naval Captains of the Seven Years’ War. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012.

“Portable soup (dried soup block).” Royal Museums Greenwich. https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/6061.html

Rupp, Rebecca. “The Luke-Warm, Gluey, History of Portable Soup.” National Geographic. September 2014. www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/the-luke-warm-gluey-history-of-portable-soup.